Bruce Schneier, guru of cybersecurity, explained in his latest book, ‘Data and Goliath’ how we have lost the battle of privacy. The giants of technology are nourished by this data to offer more and better services for users, but they do so at the cost of trying to extract all the information they can from our activity in those services and applications.

Google is the most vilified company in this regard : the voracity with which it seeks to collect more and more data about us and what surrounds us is reaching unsuspected limits, and that has made winners and losers in that particular war for our privacy.

Google, we have to talk about privacy

Google is condemned by its own business model, which is focused almost entirely on advertising. To serve advertising that suits us and is relevant to us Google must know us better, and that’s where that ambition appears to collect more and more data about us.

Google’s efforts were already questionable some time ago, but now they have become clearly worrisome. In the last months we have seen how it pursues us when we buy, when we communicate, when we take a walk(even if we deactivate the GPS) or when we use our WiFi network.

The problem is not just that they collect data. In fact, most people have already assumed that by using Google’s search engine, their Chrome browser or their webmail client Gmail is giving up some of their privacy so that Google can continue to offer those wonderful products and services-which they are in many aspects – for free.

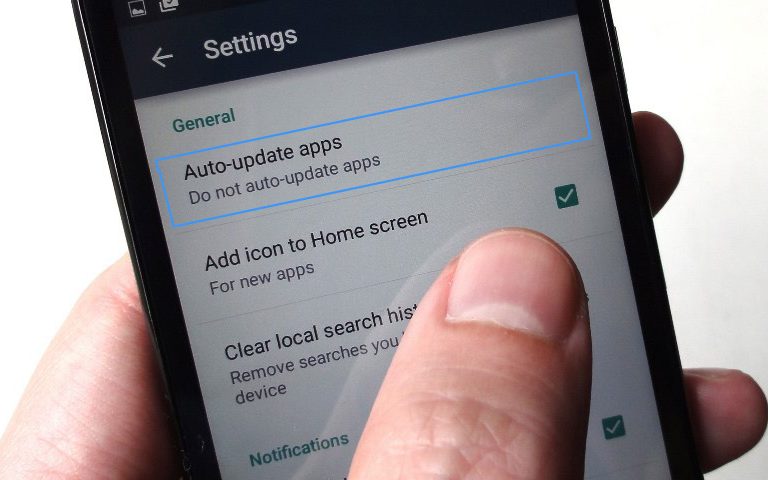

The real problem lies in the fact that Google (like many other companies) fails miserably in its way of communicating what it collects and what does not, and for what reason. It also fails to provide information on how to turn off those options and the consequences for the user, so most people simply do not know how much privacy is giving way and what to do to minimize the risks.

Here Google, and the speech is valid for many other large (and not so big) technology, should make a radical effort to be much more transparent and offer much more control over that data collection. What data does Google collect from my searches or my use of Gmail? With what reason? Where do these data go, how long are they saved, what kind of encryption process is used? And most important: how do I deactivate that collection partially or totally, and what consequences does it have to do?

Without that information, the only thing we can deduce is that the balance between privacy and comfort does not exist. Or choose one thing (use Gmail and assume that they will “read my mails”) or the other (I do not use Gmail, and I forget the email or I use more respectful alternatives with my privacy as Protonmail).

Continue Reading: Google has faced two artificial intelligence systems, will they fight or work together!

If you do not pay for the product, you are the product (and if you pay, too)

Here comes the famous ‘if you do not pay for the product, is that you are the product’ to which many refer when they talk about the free services of Google (or Facebook, or Microsoft, or Twitter, or many others) that we use daily . The phrase, although striking, can be dismantled.

The developer Derek Powazek years ago with a series of examples indicating that different companies use different models in which it does not matter if the services are free or paid, because the data collection and the presence of advertising follows very different balances …

That you pay does not mean that you are not the product. Cable TV companies take our money and sell us to channels, magazines take our money and still sell advertising, banks and credit cards charge us for having our money. Any store that has a “loyalty card” charges us for products but offers discounts in exchange for the ability to monitor what we buy. In the real world we have routinely become “the product”, even when we pay.

The argument of Powazek is forceful and real, and the truth is that it does not matter whether we pay or not: it is likely that in both cases we will end up becoming the product. It is true that some companies have more interest than others in collecting data, but their business models are also based on that collection.

A winner, many losers

As we anticipated at the beginning of this reflection, that attitude of Google has reached hard defensible limits, and here the big losers are of course users, exposed to policies that we hardly understand or can control.

We are not the only losers, because Google’s traditional partners, companies that use Android or Chrome OS, are also affected by the problem. Smartphones, tablets or Chromebooks from Samsung, LG, Xiaomi, Sony, Acer or many others are just another vehicle for data collection for Google, which is nourished by that huge market share of Android.

Obviously these companies are not exempt from fault, and many of them already collect additional data for their own benefit. Xiaomi does it, Samsung does it (a lot), LG does it, and Sony does it. The collection goes beyond Google and its services and products: Nintendo does it, Amazon does it, Facebook does it and, of course, Microsoft does it. Here the one who does not run flies.

They do it with the same purpose as Google, and here once again we are the users who do nothing but lose battles. It does not matter that we brandish that “we have nothing to hide”, because that argument is also easily dismantled. We simply cede and constantly sacrifice privacy in exchange for free services or comfort.

Interestingly there is a “great” winner of this battle, and that is Apple. For some time, the company led by Tim Cook has become a champion of privacy, while those companies that depend on Android (Samsung, LG, Xiaomi or Sony) are dragged by the side effects of Google’s greed for information ( and his own).

The defense of privacy is patent at the public level: Apple’s recent battles with the FBI and its constant discourse in this area are proof of that. But it is also that Apple has a business model totally different from Google, and that means that they do not need (so much) our data. From there to say that they do not collect them, yes, half a world.

+ There are no comments

Add yours